DAY SIX

WEDNESDAY, APRIL 5, 2023

REFLECTING WITH BUDDHIST MONKS IN THE MOUNTAINS

Today we were taking a day/overnight trip to Koyasan, an area founded by the monk Kobo Daishi who established Shingon Buddhism about 1100 years ago in the mountainous region south of Osaka. We got on a little minibus and left in the morning, stopping at a rest stop to pick up breakfast/snacks. The drive took about two and a half hours.

When we got to Koyasan, we stopped for lunch in a cute little coffee shop, Kahmi Coffee, that had a few different kinds of curry – Maho had passed around a menu on the bus and we preordered, making it easy once we got there.

Turns out that the 1100-year-old monastery where we were staying for the night, Sekishouin, was right next to the cafe, so we walked over and checked in. You take your shoes off immediately on entering the building, and they have rubber slide sandals for everyone to walk around the property.

As an introduction, we met in a prayer room with one of the monks who gave us an overview of the area and to Shingon Buddhism. I’m not sure what I was expecting, but he had a great sense of humor. (And amusingly let us know that even though there were “no photography” signs all over, who would know? 😄)

After the introduction, I took some time to walk around the main building to check out the art before finding my way to my room.

The rooms themselves were unsurprisingly minimalist, really just a thin mat on the floor with a comforter on top. I did laugh at the ancient and authentic flat screen TV.

The outer door to my room

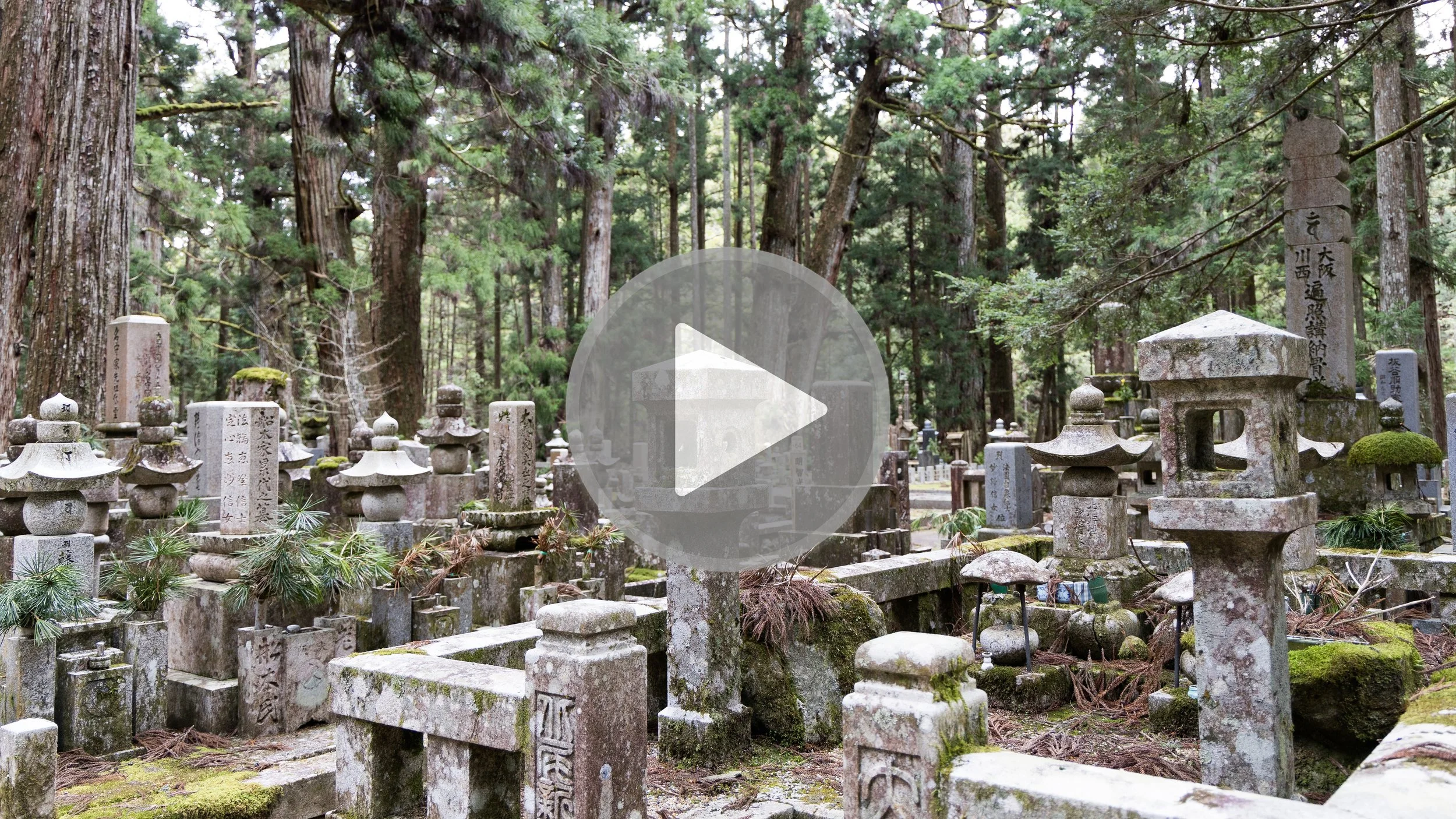

After getting settled, Helen, Allison, and I walked over to the Okunoin Cemetery, one of the most visited parts of Koyasan.

I’m not really a cemetery person, but I can totally understand why this one is a big deal. It contains between 200,000-400,000 gravestones and pagodas for important historical figures, samurai, shoguns, feudal lords and even commoners. As I soon found, current corporations (like Panasonic in my photo below) have also started to reserve space, I believe for their employees. It’s unknown how many other people are buried underneath the ones counted; there could be thousands more! Most of the cemetery (at least the part we walked) is a path that leads towards the mausoleum of Kobo Daishi himself where he rests in eternal meditation, awaiting nirvana.

Towards the beginning of the path, we happened to run into Maho who let us know that when we eventually reached the bridge to the mausoleum, the area beyond it is a very sacred space where photos, food and drink aren’t allowed.

The whole place was unexpectedly really beautiful, with one incredible statue after the next and thousands of cedar trees reaching the sky. There weren’t a ton of people there, and everyone was really respectful and silent,

One very striking and unique element of this cemetery is the large number of small statues, called Jizo, wearing knit hats and bibs. I went down a rabbit hole to try to understand the meaning, and discovered a really interesting mythology.

(Paraphrased and compiled from various Googling:) The story of Jizo Bosatsu can be traced to the 14th-century Japanese folktale, Sai no Kawara (“riverbed of the netherworld,” similar to purgatory in the Christian tradition or the River Styx in Greek mythology). It is believed that souls of mizuko or “water children”—the stillborn, miscarried and aborted—go into a kind of limbo on the banks of a rocky river and are not permitted to ascend to Paradise because their early death brought great sorrow to their parents. Here the children are forced to build stone towers dedicated to their parents and siblings to atone for their sin of causing heartache, and each night demons destroy the towers they have built forcing them to start all over again.

Jizo Bosatsu is believed to be the guardian of the children’s souls – the bodhisattva of all those trapped in this purgatory. He takes them and hides them in his sleeves to sneak them out past the demons and allow them to reach the afterlife, and has vowed not to achieve Buddhahood until all trapped in Sai no Kawara are freed.

And so parents who have tragically lost their child or fetus visit the cemetery to dress the little statues, a signal to Jizo Bosatsu that their souls are ready and waiting for him to collect them and carry them to Paradise, kept warm along the way by the cozy hats and scarves. Red is symbolic in Japan as the color that keeps away illness and danger (and demons), which is why the majority of the clothing and accessories are red.

Throughout the cemetery, surrounding the Jizo statues and in and around trees, are also little gifts, coins, flowers and other offerings that come from visitors, either in mourning for the loss of their loved one or in thanks for them being saved.

A sense of the peacefulness

The one thing I couldn’t figure out is why there is makeup painted on many of these statues, since everything I read called out their association with children. It’s oddly hard to find anything on this, but it sounds like the Jizo statues actually represent way more than just children and are created for lots of different occasions, prayers, and good fortune; so the makeup is likely applied by visiting Buddhists as a prayer for better skin!

At the back of the cemetery path, getting close to the bridge to Kobo Daishi’s mausoleum, there is a large pyramid made up of small Jizo statues called the “Mound of the Nameless,” dedicated to those who have died who have no family or anyone to individually care for their graves. The structure isn’t that old in the scheme of this sacred place—only 30 or 40 years— but it’s a poignant way to honor the otherwise forgotten.

Image from Atlas Obscura – I’m not sure why I didn’t take a picture!

Crossing the bridge to the mausoleum (and therefore putting my camera away), we walked through the building and took in the stillness and sacredness of the space.

Because I couldn’t take my phone out for the help of Google Translate it was tough to understand the meaning behind a lot of what we were seeing, but it was such a serene feeling, and smelled strongly of incense. Clearly a lot of offerings and prayer happening around us.

In front of Kobo Daishi’s mausoleum is Torodo Hall (the Hall of Lanterns), which is the center of worship for Okunoin. It’s an unassuming building from the outside, so it’s just by luck that we decided to go in, but we took off our shoes, stepped inside, and it immediately took our breath away. Walking through the aisles you can’t help but be hit by the deep spirituality of the hall with its 10,000+ eternally lit lanterns, the smell of incense, and the pure silence.

I of course respected the space and didn’t take any photos, but am secretly glad there are a few on the internet. I’m sharing one here for the sake of remembering the experience.

Leaving the hall of lanterns, the sun was starting to go down so we began making our way back through the cemetery to our monastery.

Allison and Helen wanted to explore further but I was ready to relax a little before dinner, so they kept walking into the town and I wandered through some local shops a little before going back to the room. (I was really hoping for a little lantern to take back with me, but no dice.)

In our rooms they had given us samue, which are colorful pajama-like tops and bottoms, so most of us wore them down to dinner. We all gathered in the big room where we had first gathered in the morning, and sat down on the floor along the perimeter, where they had trays with an array of shojin-ryori vegetarian food (no meat, fish, onions, or garlic).

After dinner, I think some people walked through the cemetery at night, a couple of people went to the onsen (communal hot springs bath), and others wandered the property, but I was starting to feel the fatigue of our nonstop trip so called it an early night and went back to my room to relax and get a good night’s sleep. Definitely the right call to have some down time!